Deirdre Sullivan Introduces Savage Her Reply + Mini Interview

Titles marked with a (^) are ad: affiliate links, which means if you make a purchase through them, I'll receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Titles marked with an asterisk (*) were gifted to me by the publisher in exchange for an honest review.

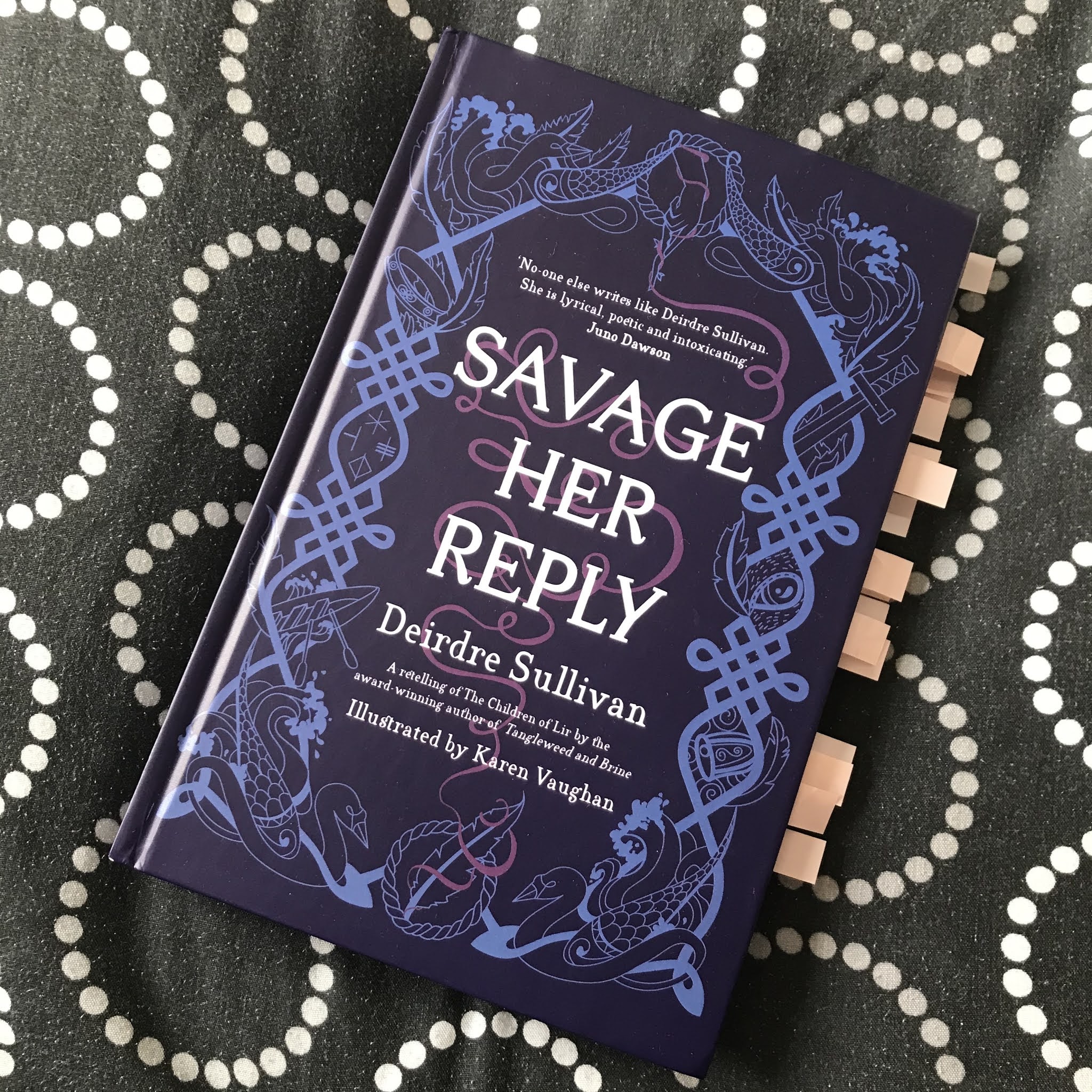

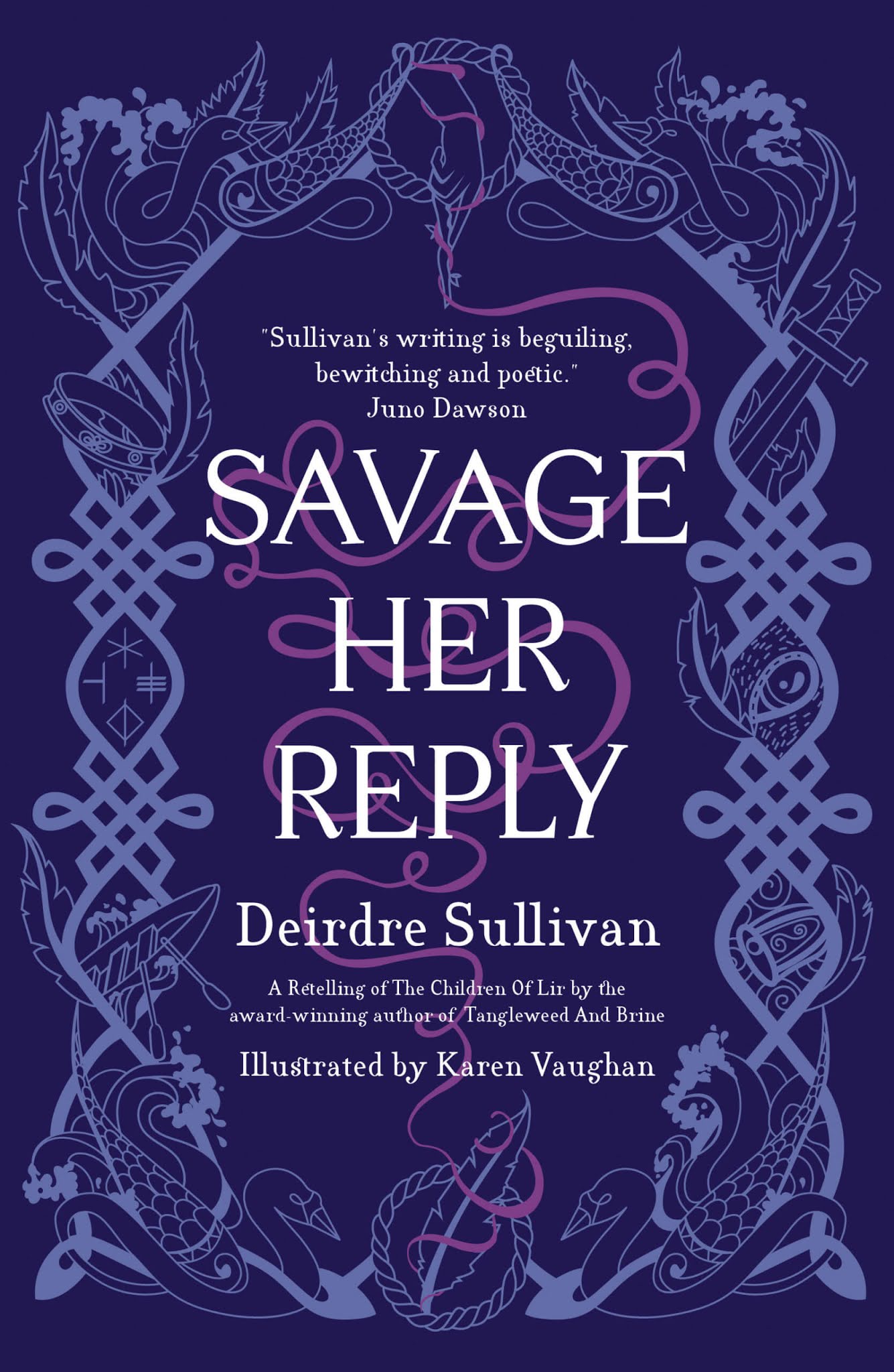

Today is my stop on the blog tour for Savage Her Reply* by Deirdre Sullivan. It's a feminist retelling of the Irish legend The Children of Lir, from the persepctive of Aífe, the story's villain. For us bloggers, this blog tour was arranged a little differently, and we got something super special. We were invited to an exclusive private Zoom meeting with Deirdre and publicist Nina, where Deirdre told us about Savage Her Reply, and we also got to ask her a few questions each, for our own exclusive element of our posts. Unfortunately, I was on holiday when the meeting took place, but it was recorded and Nina was kind enough to ask Deirdre my questions on my behalf.

So first, there's a transcript of the beginning of the meeting, with Deirdre telling us about her love of the original story, what led to her wanting to write a retelling, and her writing process - which has been edited for brevity and clarity - and following that is my mini interview with Deirdre. So Deirdre, take it away!

- and the questions about the story that led to Savage Her Reply

Initially, I had tried to tell Aífe's story in Tangleweed and Brine as one of the stories in the collection, because I was always very drawn to her. There is a book called The Children of Lir, a retelling by Michael Scott; it's got a beautiful, beautiful picture on the cover by Jim Fitzpatrick of Aífe transforming the children in to swans. It's shades of blue, and her hair is wild and red and beautiful, and she's got a kind of light around her, and she just looks so cool! And as a little girl, I took that book out of the library and I have this visceral memory of taking it back, and just looking at it and looking at the librarian, and being like, "I don't want to give this back to you!"

This photo is copyrighted to Deirdre Sullivan and used with permission.

But Aífe was always the character that meant the most to me. I always found her disappearance from the story halfway through--it was like a question mark. That question mark is what drew me to want to retell her story. She is turned into a demon of the air, which for some reason is her deepest fear. I was trying to work out what a demon of the air would be and why that would be your deepest fear. I came to a lack of connection, because as a foster child, as someone who has lost her sister, as someone who has tried so desperately to forge a connection in this marriage that she was forced into and fails, [Aífe] is a person who has time and time again sought to find space of acceptance and love in the world and been denied that. That's where I kind of thought her worst nightmare would be to forever not have that be an option.

So when I went to write it for Tangleweed and Brine^ - and I had a fair few false starts with it - it just didn't fit. They were all kind of classic Grimms' or Anderson's fairy tales, or Irish fairy tales, and the Children of Lir, it exists in a more mythic space, and at that time I thought it was a legend. When I did a bit of research in to it, I found that that's not actually true, it's a bit more complicated than that, like a lot of things are.

The Children of Lir, I thought initially, was one of our oldest legends, because you'll actually get that written down in the books all the time here, [in] introductions, you know, "This is a new retelling of one of Ireland's oldest legends," and it's not. Ireland's oldest legends are pre-Christian, and The Children of Lir is kind of an authored hybrid of myth and fairy tale, the first written down text seems approximately from the 14th Century. So even though it's--like, that is old! I'm not going to argue with the fact that that's old, [but] it's not as old as I had been led to believe. One of the reasons that I had been a little bit fooled by it was also, you know, it's the stories we tell - the stories we tell and the stories we tell about stories. But also, it draws on mythology that pre-dates the legend itself, so characters like Lir and characters like Bodhbh the Red, they exist in much more ancient texts, and they were kind of used in this, to my mind reading it, to push the Christian agenda. Because the Children of Lir are cursed until they repent, or until they take Christ into their hearts, or hear the ringing of the Christian bell, and their curse can be broken. That didn't sit too well with me either. As an Irish woman who has grown up in a nation where the Church repeatedly failed women and marginalised people, I wanted to interrogate that a little bit as well.

So I did reading for a year, and then I started writing. I set myself word count goals, so what I would do while I was intensely writing Savage is, I would write a thousand words a day - I can write more than that, but I know not too many more. I know some people write like 5,000 words in a day, and I do not know how! I'd write a thousand words a day, I would stop there--unless it was mid-sentence, because you know--then I would read legends, read folklore, or read around the different emotional experiences I wanted Aífe to feel, to prepare for the next day. I would underline different images--there's a point where her hair's artfully arranged as she's being presented to Lir, and that's taken from a legend. The colours of the cloaks were important. The comparisons that she makes are often similar to comparisons that would have been made in ancient myths, like using words like, "clouds of blood." I wanted to very much give her language of the legend that she occupies, but equally, because she's immortal, she's also modern; she kind of exists in a space where she's seen an awful lot, and that was a bit of a challenge to write. I wanted to make sure it was accessible; The Children of Lir is known very well in Ireland, but I wasn't sure how well it was known in other places. And even to me, who knew it very well and loved it, there had been surprises in different versions that I'd read, in different translations - there's the Lady Gregory, the Eugene O'Curry, there's the Michael Scott which I mentioned before. There are a fair few different versions of The Children of Lir, and in some it's Mochaomhóg the Monk, in others it's St. Patrick. So I wanted to kind of give the reader my own definitive traditional version of the story so that they could see what in particular had happened to Aífe, because while it doesn't vary hugely - she's always going to turn them into swans for 900 years, she can't change her mind about that! - there are other things that do vary. And once I had that part of the structure down, the Calligrams were the next thing.

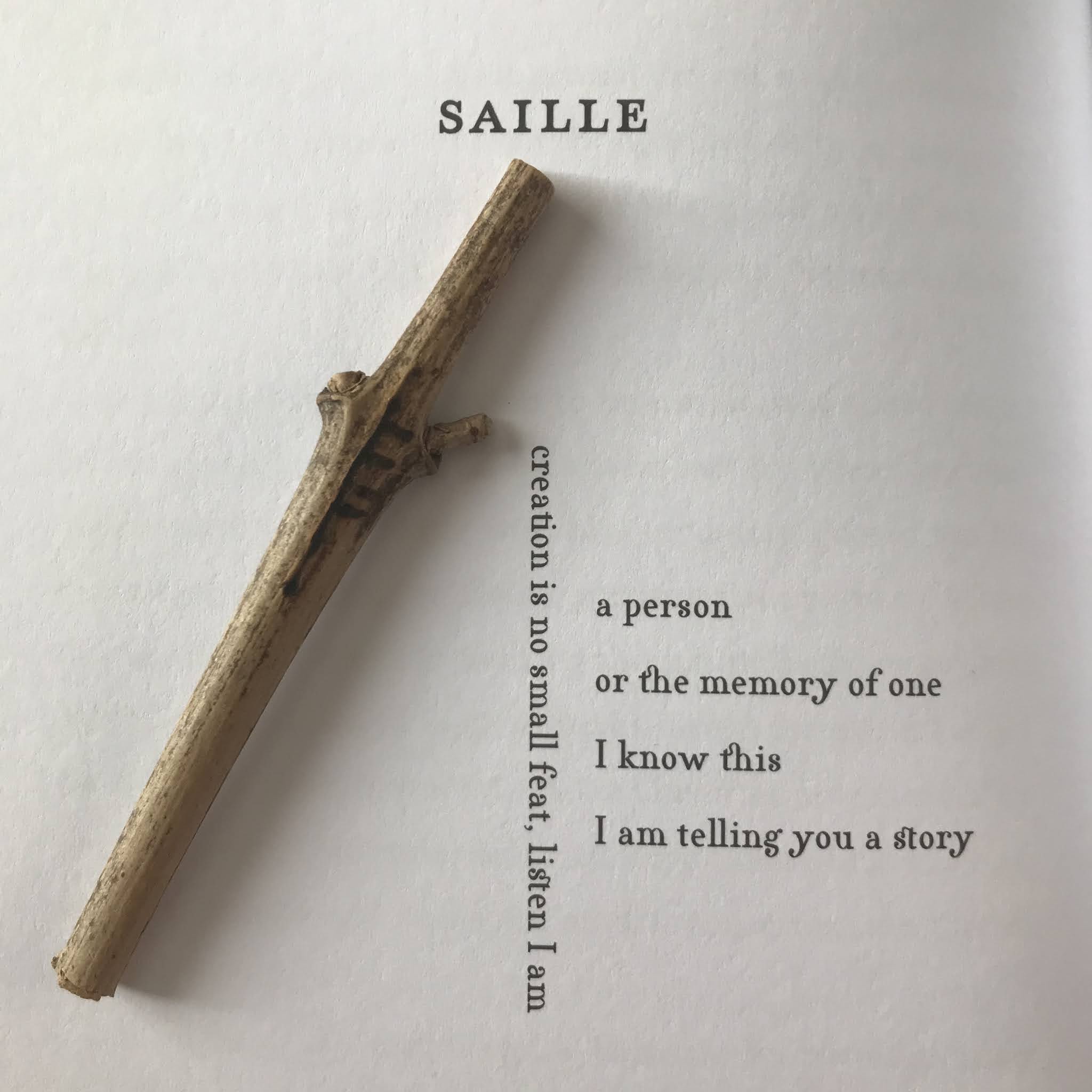

Ogham Calligrams

The rune that you would have got has one of the letters of the Ogham alphabet on it, which is an ancient Irish alphabet, but it's also more than an alphabet because every letter represents something. When I began to initially research Ogham, I thought that every letter represented a tree and people use them as runes. They do use them with that in mind, but when I started unpacking it, I realised that's not strictly the case, that there's a certain amount of cultural appropriation goung on there with people coming in and co-opting [Ogham] to tell the story they wanted to tell at the time when mysticism was growing in popularity in Britain and across the world. Every letter does represent something, but it's not necessarily a tree, it can be loads of different things. You know when you start researching something and you learn just enough to know how much you have yet to learn? It's this really fascinating mystery to me. What I wanted to do with the calligrams is, I wanted [Aífe] to rewrite the alphabet in her own voice. I wanted her to take the tools of story and make her own of them. I found for me personally it was a great way to connect to the disjointed emotional arc that she goes through because of the trauma that has been visited on her by circumstance, but also by her own choices, that she then has to live with.

The Writing Process

I mainly wrote it over the space of a year. I got the body of it done in the Summer, and then I finished it on 31st October - because I'm spooky! It was the weirdest book I ever began, because I couldn't begin it for ages. I kept having false starts. Every book I've written has been different, and it's been a different process. Perfectly Preventable Deaths, my book before Savage Her Reply, took me seven years from the first draft to the publication. This took two, but equally the writing required an awful lot more research. It was a very intense experience, and it was more all smushed together; I didn't really take breaks from Savage Her Reply. But when I initially found the beginning of the book, it literally came into my head one day, the first sentence. I sat down, I banged it all out from start to finish, and I burst into tears when I got to the last line. That had never happened to me before, it was really, really weird! And it hasn't happened to me since. I have cried while writing, I mean if you're going to murder someone or something, you know, you might as well have an odd tear or two for them! But it was proper--my husband was like, "Are ya all right?!" "It's fine! It's the words!" But it was really weird. That deep connection stayed, for whatever reason; I really felt Aífe very, very deeply, and I really hope that other people feel her, too.

[Writing Savage Her Reply was] absolutely different [to writing Tangleweed and Brine,] because Tangleweed and Brine is 13 stories, so each story is kind of--it's intense when you're writing it and working on it, but you can finish it and you can have it done. You lay it aside, you start the next thing. With this, this was supposed to be a novella! This was supposed to be less than half as long as it is! I was talking to someone recently, who'd read an interview with me, where she was like, "Oh yeah, you alluded to this tiny little project you were working on, is this it?" And I was like, "Yeah..." It just surprised me so much at every turn; the legend wasn't what I thought it was, [Aífe's] voice wasn't what I thought it would be, the arc wasn't what I thought it would be. My emotional connection to it--it really surprised me. I probably say this about every book I have that's just about to come into the world and I've worked on for year, but [Savage Her Reply] is a very special book to me.

I was on holiday when my review copy of Savage Her Reply arrived, and while lovely publicist Nina was kind enough to email me a PDF, the internet connection was just so bad where I was staying. So my questions for Deirdre - which Nina was kind enough to ask on my behalf - were based on what I knew of Savage Her Reply, and about Deirdre's retellings in general from reading Tangleweed and Brine.

When it comes to female fairy tale characters, what would you say makes a villain?

I think that intentional cruelty makes a villain. I think prioritising the position of power over the lives of other people makes a villain. And I think as well targetting the vulnerable, and cruelty for the sake of cruelty - like if people will be cruel when they know they're not going to be held accountable. I always find that a very villainous trait. I think the absence of empathy and the absence of compassion are good. But in terms of an iconic female villain, I love me, you know, wild hair and sweeping clothes, and control of the elements and all of that stuff! But I think what is actually villainous is a lot more human and a lot darker.

There's a strong focus on women's power and agency in your retellungs; a woman with power is dangerous, but a woman without is in danger. There's truth to your retellings. How do you retell these stories from a feminist angle, which still giving us something original, surprising, and dark?

I don't know, really! I really don't, I just try my best. I have all these questions going into stories, and I try to explore them. I try to find a character that feels real to me, and I try to do my best by them. That's what it's like for me as a writer.

I know [this is] not how the question's phrased, but becayse I'm a teacher, and because I write fro young adults and sometimes younger readers, you'll often get people who don't live and breathe books saying, "Oh, what lesson do you want to teach them? Or what agenda are you pushing?" I really want to keep any sort of didactic thing out of my writing. I want to ask questions, but I am not a wise person, I do not know the answers to them! A lot of the time, I'm just taking them for a walk and seeing what happens, and I'm really, really glad if that resonates with people.

In an article you wrote for the Irish Times when promoting Tangleweed and Brine - Fragmented Fairytales with a Feminine Twist - you mentioned your love of fairy tale criticism. How has your love of fairy tale criticism informed how you approach your retellings?

I suppose [they] gave me different eyes when looking at fairy tales. Writers like Marina Warner, Marie-Louise von Franz, Maria Tatar, Jack Zipes, and I the work they have done around fairy tales. That's from an academic perspective, but writers like Emma Donoghue^ and Angela Carter who have taken fairy tales and have rebuilt and reshaped them. They both showed me different tools I needed to retell.

My own photo of fairy tale criticism I own: The Uses of Enchantment by Bruno Bettelheim^, Once Upon a Time by Marina Warner^, and Don't Bet on the Prince by Jack Zipes^.

So the academics would have been, "This is how we break down, how we examine a fairy tale, and it's ok to interrogate. Here are all the different historical versions and here is how it has mutated to reflect the society in which it is being told. Here are the stories that have been supressed, this is why they were suppressed in this particular period. This writer was writing with this particular agenda, and from this particular space, which is why these details are included in the story." And I think that's hugely, hugely fascinating. Although, I do get a little like--people do it to me sometimes, I've had a couple of people write academic things on Tangleweed and Brine, and I'm like, "I'm not clever enough for a clever person to do this!"

And then writers who have excited me and compelled me, show me what's possible, like Angela Carter. Reading The Bloody Chamber^ for the first time was such a formative experience for me. It was like someone had come up to me in the library, had gone [*whispers*], "There are no rules!" and run off. And I will always love her for that.

Do Irish fairy tales and folklore inspire your witchy insterests, and if so, how?

Yeah, they do a bit. I like going to old places and places where myth and legend have taken place. There is a housing estate in Dublin with a Dolmen in the middle of it. The Dolmen is many thousands of years old, and there are just like people milling around this amazing portal tomb thing! So I will drive to random places and look at them a lot more since writing Savage.

Tangleweed kind of made me feel more connected to plants, Perfectly Preventable Deaths made me respect them more for their medicinal purposes. And what Savage Her Reply has given to me is a deeper appreciation of the landscapes of my country. I've always loved visiting old houses and places that I felt could be deeply haunted. That's my sweet spot. If I want to stay overnight in a place - could someone have conceivably haunt it? And if yes, I will really want to go there. It showed me the stories that can lurk behind fields and stones, and the people who were around before people had lives I could picture accurately. I feel like, say with The George in Dublin, or tha famine times, you have a sense of what people ate, and what they wore, and what--you know, definitely in the famine--what their worries were. But if you're going back to like New Grange, if you're going back many thousands of years, it's much, much harder to picture. And writing it, and researching their folklore and their stories, and how they were told, and how they were written down years and years ago, gave me a deeper connection to that. I think that is important, and it does nourish you in ways that go beyond writing.

Thank you, Deirdre, for such fantastic answers to my questions! It really was such a great event, and so wonderful to take part part. And Savage Her Reply is an absolutely incredible novel! So beautiful and heart-wrenching, and deeply moving. Read my rave review of Savage Her Reply, and see below for more on the book, and for the other stops on the blog tour!

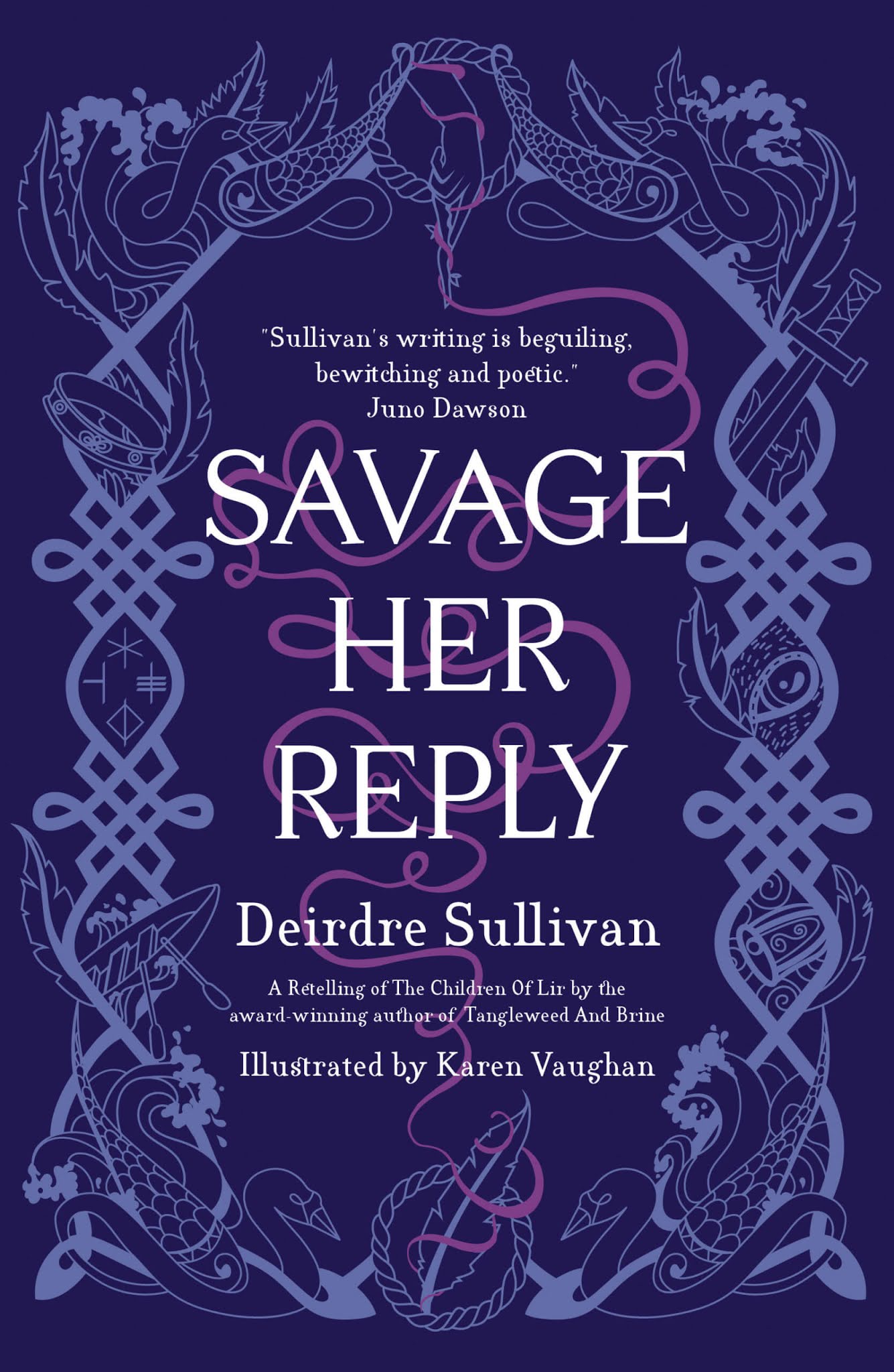

Savage Her Reply by Deirdre Sullivan* (Published 1st October 2020 by Little Island Books)

Savage Her Reply by Deirdre Sullivan* (Published 1st October 2020 by Little Island Books)

A dark, feminist retelling of The Children of Lir told in Sullivan's hypnotic prose.

You may also like:

What did you think of Deirdre's introduction to Savage Her Reply? Will you be picking it up? Have you read it already? Have you read Tangleweed and Brine? What did you think of either/both? Let me know in the comments!

So first, there's a transcript of the beginning of the meeting, with Deirdre telling us about her love of the original story, what led to her wanting to write a retelling, and her writing process - which has been edited for brevity and clarity - and following that is my mini interview with Deirdre. So Deirdre, take it away!

Deirdre's love of The Children of Lir

Initially, I had tried to tell Aífe's story in Tangleweed and Brine as one of the stories in the collection, because I was always very drawn to her. There is a book called The Children of Lir, a retelling by Michael Scott; it's got a beautiful, beautiful picture on the cover by Jim Fitzpatrick of Aífe transforming the children in to swans. It's shades of blue, and her hair is wild and red and beautiful, and she's got a kind of light around her, and she just looks so cool! And as a little girl, I took that book out of the library and I have this visceral memory of taking it back, and just looking at it and looking at the librarian, and being like, "I don't want to give this back to you!"

But Aífe was always the character that meant the most to me. I always found her disappearance from the story halfway through--it was like a question mark. That question mark is what drew me to want to retell her story. She is turned into a demon of the air, which for some reason is her deepest fear. I was trying to work out what a demon of the air would be and why that would be your deepest fear. I came to a lack of connection, because as a foster child, as someone who has lost her sister, as someone who has tried so desperately to forge a connection in this marriage that she was forced into and fails, [Aífe] is a person who has time and time again sought to find space of acceptance and love in the world and been denied that. That's where I kind of thought her worst nightmare would be to forever not have that be an option.

So when I went to write it for Tangleweed and Brine^ - and I had a fair few false starts with it - it just didn't fit. They were all kind of classic Grimms' or Anderson's fairy tales, or Irish fairy tales, and the Children of Lir, it exists in a more mythic space, and at that time I thought it was a legend. When I did a bit of research in to it, I found that that's not actually true, it's a bit more complicated than that, like a lot of things are.

The Children of Lir, I thought initially, was one of our oldest legends, because you'll actually get that written down in the books all the time here, [in] introductions, you know, "This is a new retelling of one of Ireland's oldest legends," and it's not. Ireland's oldest legends are pre-Christian, and The Children of Lir is kind of an authored hybrid of myth and fairy tale, the first written down text seems approximately from the 14th Century. So even though it's--like, that is old! I'm not going to argue with the fact that that's old, [but] it's not as old as I had been led to believe. One of the reasons that I had been a little bit fooled by it was also, you know, it's the stories we tell - the stories we tell and the stories we tell about stories. But also, it draws on mythology that pre-dates the legend itself, so characters like Lir and characters like Bodhbh the Red, they exist in much more ancient texts, and they were kind of used in this, to my mind reading it, to push the Christian agenda. Because the Children of Lir are cursed until they repent, or until they take Christ into their hearts, or hear the ringing of the Christian bell, and their curse can be broken. That didn't sit too well with me either. As an Irish woman who has grown up in a nation where the Church repeatedly failed women and marginalised people, I wanted to interrogate that a little bit as well.

Writing the Story

So I did reading for a year, and then I started writing. I set myself word count goals, so what I would do while I was intensely writing Savage is, I would write a thousand words a day - I can write more than that, but I know not too many more. I know some people write like 5,000 words in a day, and I do not know how! I'd write a thousand words a day, I would stop there--unless it was mid-sentence, because you know--then I would read legends, read folklore, or read around the different emotional experiences I wanted Aífe to feel, to prepare for the next day. I would underline different images--there's a point where her hair's artfully arranged as she's being presented to Lir, and that's taken from a legend. The colours of the cloaks were important. The comparisons that she makes are often similar to comparisons that would have been made in ancient myths, like using words like, "clouds of blood." I wanted to very much give her language of the legend that she occupies, but equally, because she's immortal, she's also modern; she kind of exists in a space where she's seen an awful lot, and that was a bit of a challenge to write. I wanted to make sure it was accessible; The Children of Lir is known very well in Ireland, but I wasn't sure how well it was known in other places. And even to me, who knew it very well and loved it, there had been surprises in different versions that I'd read, in different translations - there's the Lady Gregory, the Eugene O'Curry, there's the Michael Scott which I mentioned before. There are a fair few different versions of The Children of Lir, and in some it's Mochaomhóg the Monk, in others it's St. Patrick. So I wanted to kind of give the reader my own definitive traditional version of the story so that they could see what in particular had happened to Aífe, because while it doesn't vary hugely - she's always going to turn them into swans for 900 years, she can't change her mind about that! - there are other things that do vary. And once I had that part of the structure down, the Calligrams were the next thing.

The rune that you would have got has one of the letters of the Ogham alphabet on it, which is an ancient Irish alphabet, but it's also more than an alphabet because every letter represents something. When I began to initially research Ogham, I thought that every letter represented a tree and people use them as runes. They do use them with that in mind, but when I started unpacking it, I realised that's not strictly the case, that there's a certain amount of cultural appropriation goung on there with people coming in and co-opting [Ogham] to tell the story they wanted to tell at the time when mysticism was growing in popularity in Britain and across the world. Every letter does represent something, but it's not necessarily a tree, it can be loads of different things. You know when you start researching something and you learn just enough to know how much you have yet to learn? It's this really fascinating mystery to me. What I wanted to do with the calligrams is, I wanted [Aífe] to rewrite the alphabet in her own voice. I wanted her to take the tools of story and make her own of them. I found for me personally it was a great way to connect to the disjointed emotional arc that she goes through because of the trauma that has been visited on her by circumstance, but also by her own choices, that she then has to live with.

I mainly wrote it over the space of a year. I got the body of it done in the Summer, and then I finished it on 31st October - because I'm spooky! It was the weirdest book I ever began, because I couldn't begin it for ages. I kept having false starts. Every book I've written has been different, and it's been a different process. Perfectly Preventable Deaths, my book before Savage Her Reply, took me seven years from the first draft to the publication. This took two, but equally the writing required an awful lot more research. It was a very intense experience, and it was more all smushed together; I didn't really take breaks from Savage Her Reply. But when I initially found the beginning of the book, it literally came into my head one day, the first sentence. I sat down, I banged it all out from start to finish, and I burst into tears when I got to the last line. That had never happened to me before, it was really, really weird! And it hasn't happened to me since. I have cried while writing, I mean if you're going to murder someone or something, you know, you might as well have an odd tear or two for them! But it was proper--my husband was like, "Are ya all right?!" "It's fine! It's the words!" But it was really weird. That deep connection stayed, for whatever reason; I really felt Aífe very, very deeply, and I really hope that other people feel her, too.

[Writing Savage Her Reply was] absolutely different [to writing Tangleweed and Brine,] because Tangleweed and Brine is 13 stories, so each story is kind of--it's intense when you're writing it and working on it, but you can finish it and you can have it done. You lay it aside, you start the next thing. With this, this was supposed to be a novella! This was supposed to be less than half as long as it is! I was talking to someone recently, who'd read an interview with me, where she was like, "Oh yeah, you alluded to this tiny little project you were working on, is this it?" And I was like, "Yeah..." It just surprised me so much at every turn; the legend wasn't what I thought it was, [Aífe's] voice wasn't what I thought it would be, the arc wasn't what I thought it would be. My emotional connection to it--it really surprised me. I probably say this about every book I have that's just about to come into the world and I've worked on for year, but [Savage Her Reply] is a very special book to me.

Mini Interview

I was on holiday when my review copy of Savage Her Reply arrived, and while lovely publicist Nina was kind enough to email me a PDF, the internet connection was just so bad where I was staying. So my questions for Deirdre - which Nina was kind enough to ask on my behalf - were based on what I knew of Savage Her Reply, and about Deirdre's retellings in general from reading Tangleweed and Brine.

When it comes to female fairy tale characters, what would you say makes a villain?

I think that intentional cruelty makes a villain. I think prioritising the position of power over the lives of other people makes a villain. And I think as well targetting the vulnerable, and cruelty for the sake of cruelty - like if people will be cruel when they know they're not going to be held accountable. I always find that a very villainous trait. I think the absence of empathy and the absence of compassion are good. But in terms of an iconic female villain, I love me, you know, wild hair and sweeping clothes, and control of the elements and all of that stuff! But I think what is actually villainous is a lot more human and a lot darker.

There's a strong focus on women's power and agency in your retellungs; a woman with power is dangerous, but a woman without is in danger. There's truth to your retellings. How do you retell these stories from a feminist angle, which still giving us something original, surprising, and dark?

I don't know, really! I really don't, I just try my best. I have all these questions going into stories, and I try to explore them. I try to find a character that feels real to me, and I try to do my best by them. That's what it's like for me as a writer.

I know [this is] not how the question's phrased, but becayse I'm a teacher, and because I write fro young adults and sometimes younger readers, you'll often get people who don't live and breathe books saying, "Oh, what lesson do you want to teach them? Or what agenda are you pushing?" I really want to keep any sort of didactic thing out of my writing. I want to ask questions, but I am not a wise person, I do not know the answers to them! A lot of the time, I'm just taking them for a walk and seeing what happens, and I'm really, really glad if that resonates with people.

In an article you wrote for the Irish Times when promoting Tangleweed and Brine - Fragmented Fairytales with a Feminine Twist - you mentioned your love of fairy tale criticism. How has your love of fairy tale criticism informed how you approach your retellings?

I suppose [they] gave me different eyes when looking at fairy tales. Writers like Marina Warner, Marie-Louise von Franz, Maria Tatar, Jack Zipes, and I the work they have done around fairy tales. That's from an academic perspective, but writers like Emma Donoghue^ and Angela Carter who have taken fairy tales and have rebuilt and reshaped them. They both showed me different tools I needed to retell.

So the academics would have been, "This is how we break down, how we examine a fairy tale, and it's ok to interrogate. Here are all the different historical versions and here is how it has mutated to reflect the society in which it is being told. Here are the stories that have been supressed, this is why they were suppressed in this particular period. This writer was writing with this particular agenda, and from this particular space, which is why these details are included in the story." And I think that's hugely, hugely fascinating. Although, I do get a little like--people do it to me sometimes, I've had a couple of people write academic things on Tangleweed and Brine, and I'm like, "I'm not clever enough for a clever person to do this!"

And then writers who have excited me and compelled me, show me what's possible, like Angela Carter. Reading The Bloody Chamber^ for the first time was such a formative experience for me. It was like someone had come up to me in the library, had gone [*whispers*], "There are no rules!" and run off. And I will always love her for that.

Do Irish fairy tales and folklore inspire your witchy insterests, and if so, how?

Yeah, they do a bit. I like going to old places and places where myth and legend have taken place. There is a housing estate in Dublin with a Dolmen in the middle of it. The Dolmen is many thousands of years old, and there are just like people milling around this amazing portal tomb thing! So I will drive to random places and look at them a lot more since writing Savage.

Tangleweed kind of made me feel more connected to plants, Perfectly Preventable Deaths made me respect them more for their medicinal purposes. And what Savage Her Reply has given to me is a deeper appreciation of the landscapes of my country. I've always loved visiting old houses and places that I felt could be deeply haunted. That's my sweet spot. If I want to stay overnight in a place - could someone have conceivably haunt it? And if yes, I will really want to go there. It showed me the stories that can lurk behind fields and stones, and the people who were around before people had lives I could picture accurately. I feel like, say with The George in Dublin, or tha famine times, you have a sense of what people ate, and what they wore, and what--you know, definitely in the famine--what their worries were. But if you're going back to like New Grange, if you're going back many thousands of years, it's much, much harder to picture. And writing it, and researching their folklore and their stories, and how they were told, and how they were written down years and years ago, gave me a deeper connection to that. I think that is important, and it does nourish you in ways that go beyond writing.

Thank you, Deirdre, for such fantastic answers to my questions! It really was such a great event, and so wonderful to take part part. And Savage Her Reply is an absolutely incredible novel! So beautiful and heart-wrenching, and deeply moving. Read my rave review of Savage Her Reply, and see below for more on the book, and for the other stops on the blog tour!

Savage Her Reply by Deirdre Sullivan* (Published 1st October 2020 by Little Island Books)

Savage Her Reply by Deirdre Sullivan* (Published 1st October 2020 by Little Island Books)A dark, feminist retelling of The Children of Lir told in Sullivan's hypnotic prose.

Aife marries Lir, a king with four children by his previous wife. Jealous of his affection for his children, the witch Aife turns them into swans for 900 years. Retold through the voice of Aife, Savage Her Reply is unsettling and dark, feminist and fierce, yet nuanced in its exploration of the guilt of a complex character. Voiced in Sullivan's trademark rich, lyrical prose as developed in Tangleweed and Brine - the multiple award-winner which established Sullivan as the queen of witchy YA. Another dark & witchy feminist fairytale from the author of Tangleweed and Brine. From Goodreads.

Book Depository^ | Goodreads

What did you think of Deirdre's introduction to Savage Her Reply? Will you be picking it up? Have you read it already? Have you read Tangleweed and Brine? What did you think of either/both? Let me know in the comments!

If you enjoyed this post,

please consider buying the books using my affiliate links, and following / supporting me:

Bloglovin' | Twitter | Goodreads | Ko-Fi

0 comments:

Post a Comment