How did you come up with the idea for The Miseducation of Cameron Post?

How did you come up with the idea for The Miseducation of Cameron Post?There were actually many ideas that propelled and shaped this novel during the years that I was writing it. I don’t think I can pin the whole book down to one idea or a-ha moment. I didn’t say to myself one day, or even one week, “Well this is the big idea, this is the story I have to tell.” This novel is really a collection of disparate ideas working, I hope, in chorus. It was my first novel, and so there was just so much I wanted to “get at” with it. I knew, early on, that I wanted to write a great big coming-of-age story that spanned several years of a character’s adolescent life, and I also knew, early on, that this main character would be gay—that part of the novel would be about her burgeoning queer sexuality. In addition, I knew that I’d set at least part of the story in eastern Montana, where I grew up, because that landscape just has a way of seeping into you, and I wanted to do that landscape, that place, justice, in a novel. I also figured out, pretty quickly, that the book would be a voice-driven first person novel, which told me a lot about how to write it, how to approach the material. But other aspects of the novel came much later, after lots of starts and stops and dead-ends. I was several months into working on it before I realized that Cam would be sent to conversion (or reparative) therapy. I made that choice after I learned about Zach Stark, a sixteen-year-old from Tennessee whose parents sent him to a conversion therapy summer camp (this caught the attention of the national media after Zach Stark posted about this on his then-myspace page). It was that story that got me to spend months researching conversion therapy, and all of that research shaped so much of what ended up in the novel.

You yourself are from Miles City, Montana. How much of Cameron’s experience of her home town – the events, the views - is based on your own? Are there any aspects of the first half of the story that are semi-autobiographical?

The easy answer here is yes, absolutely. In the novel there are locations—the abandoned hospital and the lake Cameron lifeguards at; events—the Bucking Horse Sale, even the swim meets (I’m still an avid swimmer); and a fairly distinctive sense of place—the landscape, the weather, the views and culture—that I culled from my own experiences growing up in eastern Montana. This novel is at least partly a complicated sort of love letter to my adolescence there. I have great and lasting affection for my hometown, despite the challenges of growing up queer there during the 1990s. But because of some of those challenges, I was also able to draw on memories of my own feelings of guilt and shame and fear about my early crushes and attractions, though the specifics of Cam’s situation—her orphan status, her relationships in the novel—are completely invented. In lots of significant ways I’m no more Cameron Post than I am Lindsey Lloyd or Aunt Ruth or even Coley Taylor—all of those characters came from parts of me and then were invented, imagined, into fuller selves.

The death of Cam’s parents isn’t just an event that happens at the beginning of the book that makes Cam feel guilty, but something that comes up again and again as Cam grows up. Although they are absent from page one, they are conspicuous because of their absence in Cam’s life. Why did you decide to have their deaths be a reoccurring theme in Cam’s self-discovery?

I think your question speaks to the kinds of complexity of situation that I was hoping to chronicle in this novel. Yes, Cam’s parents die in the very first chapter, readers never even meet them in scene, just in some very small flashback moments, but I didn’t want to simply “use” their deaths as a plotpoint for her story, because that’s not the way we actually experience the death of someone close to us, it’s something much more significant and difficult to “get around.” Reconciling the death of someone close to you takes time, and during all those hours and days, the person’s absence creeps up on you in surprising ways. You can grieve and cope and still feel a hole in the place where those relationships once were. So much of Cam’s coming-of-age process is about figuring out, I think, what it means to no longer have parents, which means that she has to figure out what they really meant to her while she did have them—the ways in which they’d already influenced her. This process of understanding what they meant to her, and maybe what she meant to them, and how all of that shapes her identity, or might shape it, it’s typical, certainly, as a part of maturation, but usually we’re doing some of that work while our parents are still alive. Given that Cam’s parents suddenly die, this process is really forced upon Cam so specifically and powerfully, and at a young age. And if you couple that with the guilt she feels about their deaths—which is, really, a pretty childlike kind of guilt, but still, that she feels real shame about kissing a girl at the very time of their deaths—well that just makes things all the messier for her.

There are many different views of homosexuality in Cameron Post, though most are similar. However, I had never come across the idea that homosexuality actually doesn’t exist. Did you have to do any research that sparked these various views? Did you do any research for any other aspect of the book?

Surprisingly, or maybe not, there are many people whose beliefs about homosexuality as an identity-feature or “valid” sexuality are essentially reducible to “it doesn’t exist.” These people recognize that some members of a society may feel attraction (romantic, sexual, both) to people of the same sex, but they see those attractions as either a sin, a mental disorder, or both. The point, for these people, is that such attractions are something completely undesirable and abnormal—something to be treated or just outright condemned (through use of various punishments, if necessary). If this is your viewpoint—or even some watered-down version of it—if you believe that the only “godly” relationship is a heterosexual marriage between adults for the purposes of procreation, and that any same-sex relationship or attraction is a sin or sickness, then of course you’d find it appalling that there are, say, LGBT rights groups or organizations, because you see these as methods of advocating either a mental disorder or a perversion, a sin. Because I did all kinds of research into conversion/reparative therapy—and the various religious and (supposedly) secular organizations that support such “therapies” (emphasis on the scare-quotes), I came across all kinds of troubling (to me) views about sexuality and gender, in general—not just homosexuality, but all sexuality in its many complex manifestations. So much of it though, does come down to certain people’s desire to reduce all sexual behaviour and attraction, outside of a heterosexual marriage, to sin—sin, sin, sin. And, in the case of same-sex attraction and behaviour, it becomes (because of a few selective and contextually-lacking Biblical passages) perversion and sin.

My experience of researching this conversion therapy was often upsetting and always baffling. There’s absolutely zero credible (rigorous/thorough) scientific evidence to suggest that such “therapies” are effective at changing attraction or desire or identity in the least. And, in fact, there is much evidence that such “therapies” cause all kinds of harm to those who partake in them. (You can reference the American Psychological Association or the American Psychiatric Association—or a whole host of other, credible, scientific organizations—for studies and statements about this very topic).

Considering how much negativity there is towards homosexuality in Cameron Post, did you find it difficult or depressing to write?

Considering how much negativity there is towards homosexuality in Cameron Post, did you find it difficult or depressing to write?Certainly there were difficult scenes to write, moments that I wanted to render as authentically as possible, and they were taxing on me as a writer. (The “apartment” scene with Cam and Coley and several of the scenes at God’s Promise were tricky, tiring, just plain hard.) But I think, despite the many challenges that Cameron encounters, she still maintains a kind of hopefulness, a kind of bravery of spirit or selfhood, that gives some sense of optimism to the novel (I hope). She is, after all, the person telling the story, and Cameron is, ultimately, a survivor—she gets through, she rallies. This novel takes place twenty years ago, and that world is not the world of today—in substantial ways, really—when it comes to the national conversation about LGBTQ rights and identity. There is much, much more LGBTQ visibility today than there was in 1992, but even beyond that, there are significant instances of social and political change that have improved the lives of lots of LGBTQ people. Don’t get me wrong—things are not perfect, but they’re unquestionably improved from Cam’s world. But, I mean, that was sort of the point, you know? I wanted to chronicle that time and place, and to do so truthfully I had to write about some hostile views. In that way, this novel feels pretty historical—the 20 years between then and now have been a long and significant 20 years in terms of LGBTQ rights and visibility.

Religion and religious views on homosexuality play a huge part in the novel. Are you religious yourself? If so, what are your religious beliefs when it comes to sexuality? How do you correlate the two?

I’m spiritual but not religious, at least not in terms of organized religion. I was raised Christian (Lutheran and then later Presbyterian). My wife was raised Catholic (at least early on). I have very religious members of my immediate family. We all get along and love each other and eat Christmas dinner together. I actually quite adore the pomp and circumstance of some church services, the liturgy--the hymns, the standing and sitting, the repeating of texts, the lighting of candles—but I don’t put much stake in any of that, I just enjoy it for its communal and aesthetic purposes. I respond to, respect, many of the tenets of Christianity, but certainly not the way those tenets are enacted by certain believers. I don’t have any specific religious views that correlate to my experience (or views) of sexuality. I think, pretty simply, that love is the highest power, and that the things that come from love are good things.

During her miseducation, as well as negative views on homosexuality, there are also views about what is considered “gender appropriate” activities/behaviours. There were many views in Cameron Post that had me raging, and this is one of them. It’s not an attack that is specific to just the LGBTQ community, but to anyone who isn’t/doesn’t act as feminine/masculine as they "should". I was incredulous!

Even your question itself gets at the inanity of this kind of thinking, and yeah, absolutely, it’s completely frustrating—what does it even mean to “act as feminine/masculine” as one “should?” Says who? According to what? Why “should” a person with a particular set of body parts be expected to enact or perform this or that kind of behaviour, wear this or that kind of dress? Your use of the word “act” gets at just how many of the trappings of gender are really performed, enacted, certainly not innate. The reason that so many of these “therapy” programs spend so much time on gender modelling is because it’s much easier to condition someone to speak and gesture a certain way, to wear certain clothing, than it is to actually change their feelings of attraction and desire.

As much as the last pages of Cameron Post are an end, it’s also a beginning. Without giving any spoilers, why did you choose to end the book where you did? Is there a second book in you, or will Cameron Post remain a stand alone?

Cam comes to a specific kind of understanding about herself, about what she’s been through, at the end the novel. She does this, not surprisingly, at a location that has all kinds of resonance to her in terms of her relationship with her parents, her family history. She even stages a kind of goodbye to all of those experiences—a kind of ritual of closure, I guess. (She knows it’s a little silly, this ritual, but I think we often are able to acknowledge that something is silly or goofy and then partake of it anyway). She’s come through a real range of experiences by this point in the novel, and each of those experiences has shaped her in some crucial way, and she’s ready, really, to move on—particularly from beyond the shadow of her parents’ deaths. For a lot of the novel, Cam is waiting for the other shoe to drop. She keeps waiting for judgment, I think, from God, from something, that firmly convicts her for those deaths, her role in it. And part of her is also waiting to be let off the hook, once and for all. So much of her process of maturation is realizing that she has to stop looking for black and whites, for simplistic answers to vast and complicated questions.

I would certainly love to tell more of Cam’s story one day—I have a couple hundred pages toward that end, actually, picking up from where this novel ends. But I don’t have any specific plans to write that book right now. I think this book does offer closure. It doesn’t end neatly, necessarily, but where’s the realism in every loose end being tied with a bow?

On your route to publication, did you encounter any difficulties finding an agent or publisher due to Cameron’s sexuality?

Nope, never once. Both my agent and my editor were always completely behind Cameron’s story, as is—they never encouraged me to tone it down or change it, make it more palatable to a wider audience or, I don’t know, “less queer,” in any way.

What is your opinion on how YA novels of today deal with LGBTQ themes?

There are really so many phenomenal YA books with LGBTQ characters and themes and situations right now—it’s like queer YA boom time: I’m continually inspired and excited by what I see getting published and noticed. Novels by David Levithan and Malinda Lo and Jacqueline Woodson and A.S. King and this year’s most multi-multi award winning YA novel (a Stonewall winner, Printz finalist, Lambda winner): Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Saenz. I’m always going to be pushing for books with representations of more diversity of situation and culture and sexuality, class, background, but I’m thrilled at the kinds of really compelling LGBTQ YA books—both fiction and nonfiction—on the shelves right now. Many of these books are funny and sometimes heart-breaking contemporary novels, but really, there are striking examples of queer characters across genres, which is even more exciting to me. Is it enough? Not yet. But I’m delighted about where we’re headed.

What are you working on at the moment?

A contemporary YA told from the dual perspectives of its two clashing protagonists as they work to make a controversial film about, well, a boarding school and 1900’s girls in love with other girls (romantic friendships), and ghosts…maybe—maybe there are ghosts, I can’t tell you for certain because it would ruin the mystery of said ghosts. I’m the worst person ever to ask for an “elevator pitch.”

Thanks for including me (and Cam) in your YA Pride Month!

Thank you, Emily, for such a long and detailed interview! Aren't her answers just brilliant?! Be sure to check out Emily's website, and read my review of The Miseducation of Cameron Post.

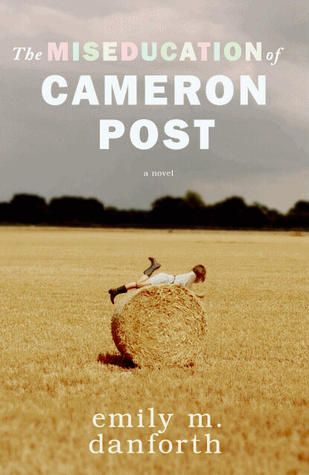

Great interview! I loved The Miseducation of Cameron Post, including the setting, which surprised me(originally, I kept avoiding this book because of the hay bale on the cover).

ReplyDeleteGlad you enjoyed the interview! :) Such a great book! Haha, how strange. I think it's such a beautiful cover!

Delete