Looking Glass Girls

Looking Glass GirlsI loved Alice as a child. But I was very specific about my love: not Alice from Alice in Wonderland, Alice from Alice Through the Looking Glass. I secretly thought they were two different girls—Wonderland Alice chased a rabbit, but she didn’t know what would happen. She didn’t choose it. It wasn’t on purpose. Looking Glass Alice spent a long time thinking about the possibility of another world on the other side of that mirror, and then she chose to leave her own house and step into that world. She wanted to be a Queen. She moved through Wonderland not because she was desperate to get home, but because she had a goal. I loved Looking Glass girls. I still do.

But you’re right when you say that Alice has something of an agency problem. Things happen to her, she doesn’t always interact so much as let Wonderlanders run roughshod over her, she experiences, rather than struggles or battles the way we expect modern heroines to do. She is wonderful, but so dreamy and proper, becoming all the more proper as her environment grows more bizarre. Alice is very much of her time. She is a Victorian child, a female one, with the weight of a whole empire’s worth of cultural expectations on her.

I could never claim to have equalled Carroll—Alice will outlive us all. But in the Fairyland novels I have often tried to counteract the things I found troubling in the classics I loved when I was young: that Wendy must be everyone’s mother instead of killing crocodiles with the boys, that Dorothy prefers the Dust Bowl and the Depression over Oz, that an adult Lucy and her siblings are forced to become children again, during the Blitz, during WWII. That the best adventures, the highest virtues, seemed to be reserved for boys. When I set out to write Fairyland and September, I wanted in some sense to mash up those stories, make them something different, make them something that would have made me feel brave and good when I was small.

September is a heroine—though she would never call herself that—because she wants to be a heroine. She wants to have adventures and be daring and see marvelous things like dragons and witches. She wants magic and wonder, and she’ll go after it. She doesn’t know everything, not even close, but she tries to piece everything together anyway, find solutions. She does not assume anyone will come to save her. She will have to do the saving, if saving is to be done. And some of this comes from having a loving, strong, and smart mother, a mother who builds airplanes and plays chess and taught her daughter to rely on her own abilities—especially since September’s mother isn’t often at home anymore, with the war on. That was a deliberate choice—the vast swath of dead mothers in Disney films and fairy tales always seemed so sad and upsetting to me, like mothers had to be erased before the story could begin. I wanted September to have quality parents.

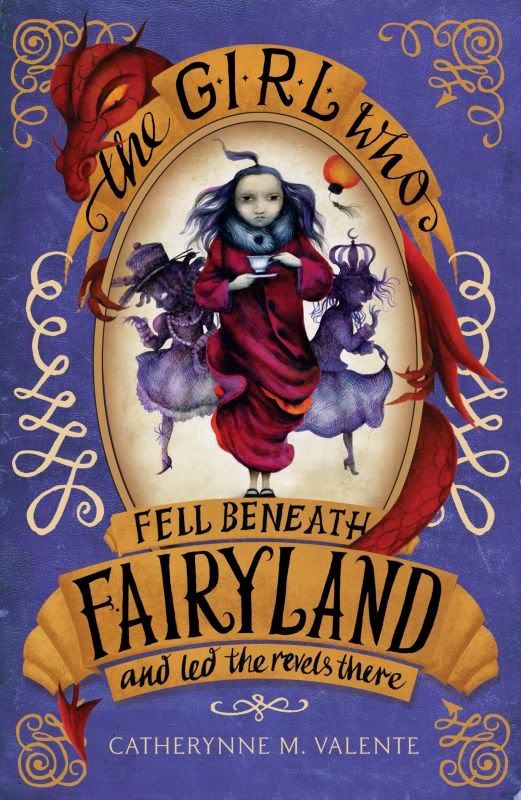

September is a heroine—though she would never call herself that—because she wants to be a heroine. She wants to have adventures and be daring and see marvelous things like dragons and witches. She wants magic and wonder, and she’ll go after it. She doesn’t know everything, not even close, but she tries to piece everything together anyway, find solutions. She does not assume anyone will come to save her. She will have to do the saving, if saving is to be done. And some of this comes from having a loving, strong, and smart mother, a mother who builds airplanes and plays chess and taught her daughter to rely on her own abilities—especially since September’s mother isn’t often at home anymore, with the war on. That was a deliberate choice—the vast swath of dead mothers in Disney films and fairy tales always seemed so sad and upsetting to me, like mothers had to be erased before the story could begin. I wanted September to have quality parents.In The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There, September sees the consequences of her deeds in the first book, and immediately sets out to make things right. She ventures into Fairyland-Below to fetch her shadow—all the wild and wicked and unpredictable parts of herself in one trickstery girl. She has to decide what it means to be good and what it means to be bad. She has to see herself clearly, as through a looking glass. Most heroines have to do that eventually. Alice, Dorothy, Clara, Persephone, Inanna.

I don’t know if September is a timeless heroine. She is also very much of our time, an intrepid girl who takes care of herself and hates injustices and believes she can do what needs to be done without waiting for anyone else to come along and rescue her. I suppose only time will tell. I know that I have always tried to make her a real girl, one who fights bravely and finds solutions and likes odd things like engines and books of fairy tales—and who also gets frustrated, impatient, says the wrong thing, gets lost and doesn’t know if she is strong enough for everything that happens to her. I have always tried to make her someone readers could see themselves in, someone who happens to Fairyland as much as Fairyland happens to her.

I would like to think she and Alice would get along, if ever they met in some distant forest, with a White Rabbit on one end and a Wyverary on the other.

Thank you, Catherynne, for such a brilliant guest post! Be sure to check out Catherynne's website, and The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland was released on 17th January 2013.

0 comments:

Post a Comment